CHAPTER IX

JOHN PAUL I,

VICTIM POPE

OPE Paul VI died on August 6, 1978. The day before his

departure for Rome, where he was to take part in the conclave, Cardinal Luciani took

a stroll through the alleys of Venice’s deprived districts. Some children

shouted merrily: «Look! Look! There goes the next Pope!» The Cardinal smiled and

answered: «Oh no! It won’t be me, it will be someone else. Let’s say a Hail

Mary together for him.1»

The episode is worthy of the fioretti of Saint Pius X2.

Despite his denials, Cardinal Luciani must have felt, in the circumstances, that

truth comes from the mouth of children, at least, that is, if he had learned

through his conversation

with Sister Lucy (as everything seems to prove) that he would become Pope.

In Rome, on August 10, the Patriarch of Venice and his secretary Don Diego

Lorenzi took lodgings in the International College of the Augustinians, situated

in the Via di Sant’ Uffizio, not far from the colonnade in Saint Peter’s

Square. He mingled discreetly among the community of friars as though he were

nothing but a humble brother.

In the mornings he made his way to the general congregations of the

cardinals. «He did everything he could to keep out of the limelight», Cardinal Gouyon would attest3.

In the afternoons he kept away from the consultations of the cardinals

preparatory to the

conclave. He would retire to the Augustinians, there to prepare the retreat

lectures he was shortly to preach to the Venetian clergy. Then he would go

for a private walk in the college gardens, saying his breviary. Sometimes he

would stop for a friendly chat with the octogenarian brother-gardener, Franceschino. Finally he would sit down on an old bench to say his Rosary.

Hiding deep within himself the graces he was receiving, Cardinal Luciani

did not disclose all those he was obtaining through the prayer of the Holy

Rosary. Nevertheless he did confide, «If one knows how, the Rosary becomes a

gaze directed towards Mary which gradually grows in intensity as one says it… It helps us

to abandon ourselves to God, to accept suffering with generosity.4»

«AFFLICTED

WITH SUFFERING AND PAIN»

The Patriarch could not think about the conclave and all the difficulties

Paul VI’s

successor would encounter without being seized with dread.

One day, in the Vatican, a Venetian who worked in the security services said

to him as their paths crossed, «Eminence, allow me to offer you my best wishes

for the conclave.

– How do you mean? That proves you wish me ill.

– On the contrary… At the 1958 conclave, Cardinal Roncalli said, “None of

you desires to become Pope, but one of you must accept

the position.”»

The Patriarch answered him, his face visibly grave, «If that was what was

needed to get into Paradise, one might just about accept it.5»

On August 22, during a friendly conversation, Senator Lino Innocenti di

Conegliano informed him that journalists were predicting that he would be the

choice of the Sacred College. The Patriarch protested, declaring that «this report

was baseless and that, if it were confirmed at the conclave, it would be a

tragedy for him»6.

The day before the conclave opened, on Thursday, August 24, Cardinal Thiandoum

invited him to dine with him at the Madri Pie Sisters in the Via Alcide

De Gasperi. «The prognosis», the Archbishop of Dakar told him, «is that the

Sacred College could well vote for you.

– That’s no business of mine», the Patriarch replied, becoming preoccupied and

pensive7.

That day he hastily wrote several notes. To Doctor Gianni Urbani he wrote:

«Even though, in the final analysis, it is the Lord who guides the Church, it is

particularly important that the Vicar of Christ be a true man of God. To play a

part in choosing him by one’s vote, to point one’s finger at someone and say to the

Lord, “Take him”, is a great responsibility which fills me with awe. Fortunately I am confident that I will not be that person, despite several

“tales” put about by journalists. “All that is pure conspiracy”, Pius X

would have said.8»

«I don’t know how long the conclave will last», he remarked to his niece Pia Luciani.

«It’s difficult to find someone

capable of facing so many

problems, problems that will become truly heavy crosses. Happily I am out of danger.

Casting one’s vote in such circumstances has

already become a heavy responsibility.9»

«Reading these lines», his niece would state, «I readily

grasped his anxiety and his fear. The fear of one who knows that, in all

probability, it is he who will be elected.10»

«His insistent claim that he was “out of danger”», remarks Regina Kummer,

«seems to have been a way of easing his mind, an attempt to free himself

from the anguish gripping him. If he had really had no belief in the

possibility of his being elected, why would he have seen it as a danger?» If he

had thought it was totally out of the question that he might be elected, it would not have occupied his mind with

such an intensity. «No, he was not “out of danger”. On the contrary, the danger

was imminent. He knew it, or at least envisaged it, and he sought to conceal his

feelings from all those who were close to him.11»

The conclave opened on Friday, August 25, 1978, late in the afternoon. When

the Patriarch set off for the Vatican, Don Diego said to him, «Eminence,

tomorrow, at this hour, you will already have received a great many votes.

– At any rate, if they make me Pope, I will refuse… I will tell them, “My

dear Cardinals, I am very sorry but you must choose someone else.”12»

After the opening ceremony, the Patriarch passed with a heavy tread along

the corridor of the loggia on the Vatican’s second floor, his Rosary in

his hand13.

The next day, at the second ballot, the cardinals’ votes swung behind him in

great numbers. «Around 4 o’clock in the afternoon, as I was going to

the Sistine Chapel for the third vote», Cardinal Malula would relate, «I met

Patriarch Luciani. I embraced him because the way the conclave was going already

showed that something was afoot. He said to me, “Tempestas magna est super

me. A great storm is over my head.”14»

At the count for the fourth ballot, he «became very pale»15

as his share of the vote increased. «Several times», recounts one prelate, «I

saw him clasp his face in his hands.16»

His colleague on his right, Cardinal Willebrands, whispered in his ear,

«Courage! When the Lord gives a burden to carry, He also gives the grace to bear

its weight.» As for his colleague on his left, Patriarch Ribeiro from Lisbon, he

whispered to him, «Don’t be afraid. There are so many people throughout

the world praying for the new Pope.17»

«As his election grew ever more likely», Cardinal Deardon remarked, «his face

became more strained. After that he displayed a kind of resignation and even a great

serenity.18»

Cardinal Pericle Felici came up to the Patriarch and handed him an envelope:

«A message for the new Pope.

– Thank you, but it is not certain yet.»

Discovering in the envelope a small Way of the Cross, the Patriarch added

that he hoped that Cardinal Felici might help him through Rome’s hazardous paths

by becoming his Simon of Cyrene: «The way of the Popes is marked by the Cross. Help this poor

Vicar of Christ to carry the Cross. Help him to ascend Calvary, for the good of

the Church, the good of souls and the good of mankind.19»

The counting of the fourth ballot was over. Albino Luciani had been elected Pope,

almost unanimously. One cardinal exclaimed, «Et exaltavit humiles. And God has

exalted the humble.20»

There then came to him the idea of taking the name Pius XIII. He had a great

veneration for Saint Pius X and he knew, as he sometimes reminded his close

associates, that the Popes named Pius had been those who had had the greatest sufferings.

But he abandoned this idea because he was afraid, as he would later confide,

that «certain groups in the Church would take advantage of this choice»21.

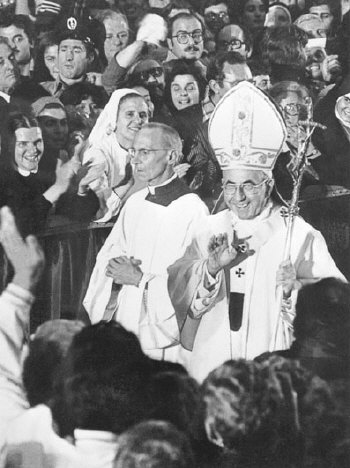

Around 6:20 p.m., having taken the name of John Paul I, he appeared on the

balcony of Saint Peter’s Basilica. Thousands of the faithful, who had hastened

to the square, were moved, struck and even in some cases overwhelmed by the

strength of his feelings and his lovely smile.

«The enduring memory is of that smile», writes David Yallop. «It touched the

very soul […]. After the gloom and the agonizing of Paul VI, the contrast was an

extraordinary shock. As the new Pope intoned the blessing Urbi et Orbi to the

city and the world, the effect was similar to a burst of bright dazzling sun

after an eternity of dark days.22»

«John Paul I’s smile», observed Raimondo Manzini, «revealed the man. It was

the expression of his gentleness, his goodness, his unalterable simplicity. It

was a smile that was virtually inexplicable, reeling as he was under the emotion

of having received such an awe-inspiring responsibility, an emotion that tore

through his soul like a subterranean flood of anxiety, but a flood that his faith, humility

and confidence in the assistance of the Almighty succeeded wonderfully in

calming.23»

On August 27, 1978, in his first message to Catholics throughout the world,

John Paul I confessed his fears and anxieties: «Our soul is still overwhelmed

when we think of the terrifying ministry for which we have been chosen. Like

Peter we seem to have stepped out on to the perilous waters and, battered by

the raging waves, we have cried out with him, “Lord, save me.” (Mt 14:30)»

But he regained his confidence as he raised his eyes towards the Immaculate:

«The Most Blessed Virgin Mary, Queen of the Apostles, will be the resplendent

star of Our pontificate.»

In this same speech we can already discern what was to become his ultimate

testament: «The Gospel invites all its sons to place their personal energies, and

even their very lives, at the service of their brothers, in the name of Christ’s

love: “No greater love is there than to give one’s life for those one loves.”

(Jn 15:13) At this solemn moment We wish to consecrate everything We are, and

everything of which We are capable, to this supreme end, right up to Our last breath,

conscious of the task that Christ has entrusted to Us: “Confirm thy brethren.”

(Lk 22:32)24»

Several days later, when he granted an audience to members of his family, he

appeared completely calm and revealed his truly supernatural spirit: «Our Lord will

come to Our aid, precisely because I have done nothing to attain this position.

So I am at peace. You also should be.25»

Nevertheless, he knew he was destined for martyrdom, or so at least we may

presume. Several of his replies or private remarks clearly seem to be

reminiscences of the mysterious prophecy that Sister Lucy had made to him.

Cardinal Sin, one of his neighbours in the conclave, had declared to him at

the opening of the

third ballot, «I am sure it is you who will be the new Pope.»

Once he had been elected, John Paul I said to him, «You were a prophet, but my

papacy will be short.26»

The day after his election, he had a conversation with his friend, Cardinal

Felici: «I have placed on my table the Way of the Cross you offered me», he confided

to him. «It has already begun.» The Cardinal remarked that at the top of the

little Via crucis could be seen the risen Christ in triumph, to which

John Paul I replied, «Indeed, but only after His death.27»

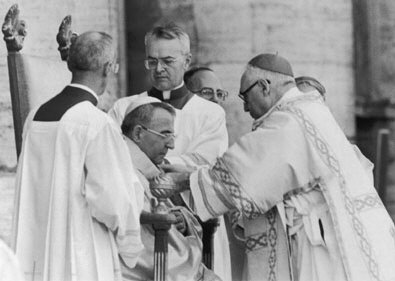

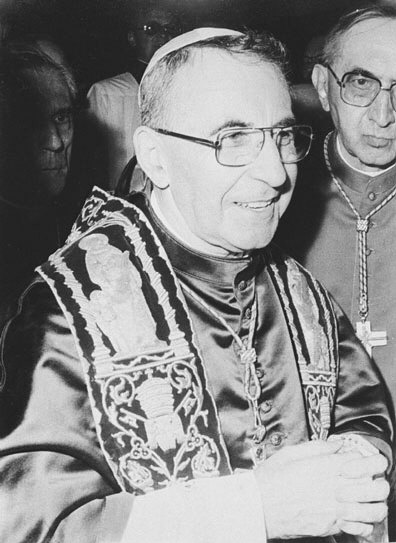

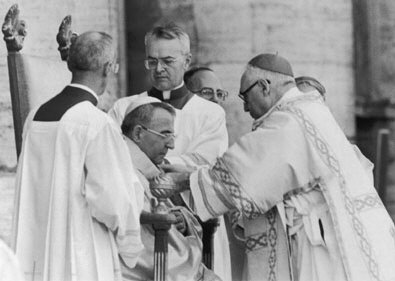

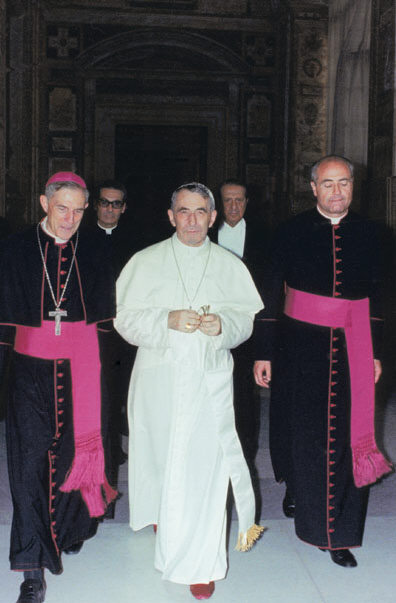

Above, on September 3, 1978, Cardinal Pericle Felici places the pallium

on Pope John Paul I at the new Pope’s enthronement ceremony (photo

Keystone).

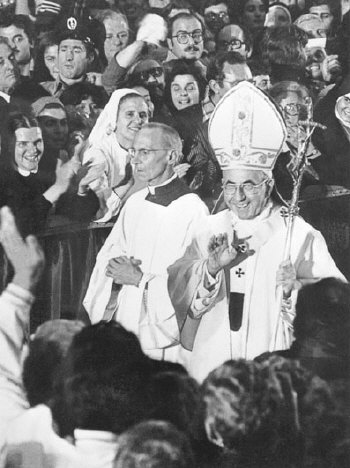

Below, during the same ceremony, Cardinal Joseph Slipyj, Archbishop of

Lviv of the Ukrainians, pays his respects to the Holy Father.

|

In his official speech to the Sacred College, on August 30, had he not

declared, «We would like to reaffirm, along with you all, a readiness to be

totally open to the inspirations of the Spirit for the good of the Church,

which each of us, at the time of his elevation to the cardinals’ purple,

promised to serve “even to the shedding of his blood”.» And he reminded the

cardinals of Our Lord’s words pronounced on the dark night of His Passion: «Take

heart, I have conquered the world.» (Jn 16:33)

Clearly John Paul I was going to be a sacrificial Pope. Regina Kummer writes,

«John Paul I was himself to be the victim, just as a grain of wheat can only

yield its fruit by dying. We should not be surprised that he sometimes asked in

distress and amazement, “Why did they elect me? They should have chosen another

prelate, one better equipped than I am.” But in God’s eyes, he was better

equipped than any other for the mission for which he was destined, he and only

he: to die like a divine seed and to bear fruit.28»

The Roman prelate who had the job of guiding him inside

the Vatican was charmed by his goodnaturedness, but also by the pious invocations

that sprang from his heart. «When I went to fetch him in his private apartment

to escort him to an audience or to a ceremony», he recounts, «he would always

ask me, “Where are you taking me?” Then he would add smilingly, “Take me

wherever you want!” And often I head him murmuring, “Be Thou my guide, O Lord!”29»

From the day after his election, John Paul I began resolutely to fulfil all the duties

of his office. Msgr. Giuseppe Caprio, Substitute of the Secretariat of

State, remembers the new Pope’s first telephone call, on Sunday, August 27.

«My telephone rang and John Paul I told me in a firm voice, “This is the

Pope here.” I was surprised by the determination and conviction with which he had

pronounced these words: he was asking me to go up to the papal apartments. After

that we saw each other two or three times a day. We worked together. I used to

sit next to him, I would submit files to him, and he would make decisions. He

was determined that his directives and orders should be followed. “If anyone

makes difficulties for you”, he would say to me, “point out that it is the Pope

who wants it.”30»

Twenty-four hours after his election, on August 27, the Holy Father took his

first decisions regarding the Vatican finances. David Yallop recounts that,

having provisionally reinstated Cardinal Villot in his office as Secretary of

State, «he instructed him to initiate an investigation immediately. There was to

be a review of the entire financial operation of the Vatican; a detailed

analysis of every aspect. “No department, no congregation, no section is to be

excluded”, Luciani told Villot. He made it clear that he was particularly

concerned with the operation of the Istituto per le Opere di Religione,

the Institute for Religious Works, generally known as the Vatican Bank.

The financial review was to be done discreetly, quickly and completely.31»

The following day, when Msgr. Martin, Prefect of the Pontifical House,

presented himself to John Paul I, he noticed that the latter was in the middle of

devoutly saying his Rosary32.

After his audience, Msgr. Martin noted in his diary, «The Pope is not taken in by

popular acclamations. He remembers those which greeted Pius IX in 1846: “And

after that came the crosses! For me the first of them have already arrived”.33»

«The first thing he asks for», remarked Cardinal Confalonieri, Dean of the

Sacred College, «is prayers, prayers that he might worthily accomplish his

mission.»

To the Superior General of the Jesuits the Holy Father wrote on August 30,

«I send you and the whole Society of Jesus my thanks for your warm words and especially for the Masses and the prayers that you have said

that the Lord may come to the poor Pope’s aid and allow him to tackle all the

hard work and terrible problems lying in wait for him.34»

On September 3, the Feast of Saint Pius X and the day of the solemn inauguration

of his own pontificate, before the ceremonies began, John Paul I spent a long time

in prayer in the Crypt of the Vatican Basilica, in front of the tomb of Saint Peter,

below the Altar of the Confession, just as Saint Pius X had done at the same moment of his election in order to calm the horrible tumult of his soul.

Everyone was waiting for him. Cardinal Felici approached and whispered in his

ear the liturgical greeting, «May the Lord make you happy on this earth!”

To which this holy Pope, regaining his composure and spirit of adoration,

smilingly replied, “Yes, happy on the outside, but if only you knew, Eminence what I am

feeling on the inside!35»

John Paul I similarly opened his soul to Msgr. Pierre Canisius van Lierde, his

Vicar General for Vatican City: «I want to let you into a secret. You see, Monseigneur, I’m always smiling but, believe me, deep down I’m suffering.36»

And so, from the beginning of his pontificate, John Paul I found himself, as in

the vision of the Third Secret of Fatima, «afflicted with pain and sorrow».

In his biography of John Paul I, published in 1988, twelve years before the

Secret was revealed, Regina Kummer wrote in a wonderfully apposite manner: «The

smile of the “smiling Pope” was not a happy smile, contrary to what one might

think, but a heroic smile, illumined by Christ. He was called to tread the way

of the Cross, in accordance with the divine decree.» Now that Sister Lucy’s manuscript

has been published, we can state that this “decree” had been recorded in

the Third Secret.

«John Paul I continued along his path, docile to the divine will. Humbly

accepting its plans, he found in the Cross his true and authentic joy. Smiling,

he climbed Calvary during those thirty-three days; smiling, he drank the chalice

of his passion. He knew himself to be in the hands of the Father and the

instrument of His designs. What a seismic upheaval this soul had to undergo!37»

AN INSPIRED CONCLAVE

Very early on the Abbé de Nantes had a presentiment of John Paul I’s special vocation. In his editorial, “Another Saint Pius X without knowing

it”, published on September 3, 1978, he wrote:

«As the 263rd successor of Saint Peter, he becomes Pope one hundred years after

the death of Pius IX, seventy-five years after the election of Pius X, and

twenty years after the death of Pius XII and the beginning of the Church’s great tribulation

– twenty years of decadence under the names of John and Paul, the very

names chosen by the new Pontiff.

«Signs? portents? Malachy calls him de medietate lunae. The half moon is the

symbol of Venice, the gateway to the East, from whence he comes. But one should rather

interpret it: from the split in the Church. A sign of woe. Whoever lives shall

see. Here is something more serious though. At the very hour in which the Pope was

elected, there took place the first showing of the Holy Shroud in Turin, the

exhibition of the Holy Face of Jesus Crucified, the memorial of His Passion and

the proof of His Resurrection, in the presence of 80,000 people. The Pope is our

“sweet Christ on earth”, he is sometimes another Crucified One, like Saint Peter.

Whoever lives shall see.38»

However, above all it was a sense of joy and exhilaration

which

gripped the

Abbé de Nantes and filled his heart the day after the new Pope had been elected. It seemed like the good tidings that he had been

awaiting for almost

twenty years. Under the title “An Inspired Conclave”, he wrote:

«According to the Roman correspondent of the Figaro, “a fair number of

cardinals, from the time of their arrival in Rome, had not concealed their

desire to elect a Pope capable of continuing the work of clarification demanded

by Paul VI at the Consistory of May 1976 and of restoring, if necessary, a little

domestic order.” Right from the beginning these cardinals had voted for the Italian

candidate recommended to their vote by the Roman cardinals in the Curia39.

But the fact that two thirds of the assembly, perhaps even a unanimity40,

should have rallied behind him without obstruction, without tumult, is mysterious and

indeed quite extraordinary.41»

«The conclave had been expected to last a long time», said Cardinal Lorscheider.

«However, the habitual opposition between conservatives and

progressivists was brushed aside. This was truly down to a providential intervention

by the Holy Spirit.42»

The Abbé de Nantes continued: «Without denying the College of Cardinals its

surprising, indeed amazing merit, one must truly talk of a miracle in connection

with this rapid, unanimous conclave and this general satisfaction throughout the

whole Church. It is as though the election and the humble appearance of the new

Pope had caused a grace of renewal – I was going to say an exorcism – to pass

over the world, everyone feeling and showing themselves to be better, happier,

more united, and in some manner, liberated. It is though there had been a

miraculous conversion of hearts. Msgr. Etchegaray was correct when he spoke of

“the massive confidence of the electors and, beyond the conclave, of all

Catholics. It is a sign of hope for the Church to see a Pope elected in these

conditions.” It is wonderful, it is truly encouraging to think that the cardinals were

won over by virtue, even more so by the faith of one of their peers. A faith

that is firm,

a virtue that is humble and prefers to remain hidden but is all the more visible for

that.43»

Our Father Superior was overjoyed because he discerned the clear signs of a

Catholic renaissance, one that John Paul I was already in the process of

implementing.

«This Pope, pious and firm in the faith, so good and so gracious, through his

appearance alone has restored the heartfelt unity of the Christian people

over that which is essential, namely the worship of God, faith in Him,

personal piety, and the practice of the virtues, especially fraternal charity. And

the Church felt she was coming alive again, freed from the shackles of the

postconciliar novelties, the tyranny of the reformist intellectuals and the

intolerable demands made by the opening to the world. Was it really so simple

after all to be a Catholic? The Pope’s smile showed that it was; it preached that it

was a joy, a real happiness.

«To the applause of the whole Church, John Paul I was restoring that religion

of all time which we had been defending against the tide for twenty years – and

openly! – in the face of the all-powerful conciliar and postconciliar revolution.44»

The smile, and even happy laugh of John Paul I, occasionally shot through

with the keenest emotion, «was not indicative of a joking or carefree

attitude. It was a communicative demonstration, an invincible preaching of

supernatural faith, hope and charity. Did he not hold up as an example, on

September 20, “those joyous and energetic saints” who make us overlook, during

the catastrophic periods of the Church, “any over-pessimistic affirmations and

tendencies? Saint Thomas Aquinas, for example, ranks iucunditas among the

virtues, that is the ability to convert into a joyous smile – in an appropriate manner and

degree – what one has seen and heard. In keeping with the

joyous news announced by Christ, in keeping with the hilaritas

recommended by Saint Augustine, Saint Thomas thus imparted a note of joy to the

Christian life and invited us to draw good cheer from the pure, wholesome joys

that we encounter on our way.”

«John Paul I had hit the nail on the head. Behind all the official

declarations of optimism, the faithful could not take any more of the climate of failure

and the collapse of the past ten years. They reacted to this smile with a tremendous

ovation which reverberated to the four corners of the earth. For this smile, this

laugh, were in their own way an affirmation of heroic self-giving, of trust in

God, in the Church, in all of us, and of love.

«Speaking to his people in Saint John Lateran’s on September 23, he said, “It

is the law of God that one cannot do good to anyone unless one love him first.

That is why Saint Pius X exclaimed on the occasion of his enthronement in Saint

Mark’s, What would become of me, Venetians, if I did not love you? Well,

I say the very same thing to you Romans.”45»

THE CATECHIST POPE

«It is a remarkable fact», noted the Abbé de Nantes, «and one we should keep

in mind in the dark times that will soon be upon us, that the satisfaction

manifested by everyone is accompanied by a lucid, premonitory and equally unanimous judgement concerning the person of John Paul I.

Everyone knows

who the newly elected pope is; he is the man of their choice and they accept him. He is

an “enlightened realist”, the opposite of a benighted utopian. “He has the

face of an honest man”, wrote the Venice Journal of their new Patriarch in 1969.

“He is a wise and saintly man”, today pronounces Cardinal Lercaro. Beneath this

smiling face, in this truly lovable holiness which reveals the fervent disciple

of Saint Francis de Sales, all have seen, admired, accepted and loved these two

major virtues: a doctrinal rigour and unbending morality, tempered by a great

kindness towards people and especially the poor.46»

The true religion appeared or rather radiated from the gestures, prayers and

words of the Holy Father.

«I will make few speeches», he had warned. «They will be short and within the

grasp of everybody. I will make use of all forms of collaboration, but I wish to

write my speeches myself.47»

John Paul I was always inclined to improvise, and that is why his allocutions

were not exactly the same as those that had been prepared and which appeared the

following day in L’Osservatore

Romano.

He had renounced the use of the sedia gestatoria. But the faithful were

disappointed not to be able to see him, especially as John Paul I was of small

stature: 1.67 m. So he took it up again from September 13.

His public audiences attracted an ever more numerous crowd: there were twenty

thousand people on September 27, and on that day the audience had to be held

twice.

The Pope inspired the humble faithful with enthusiasm by the very style of

his allocutions which were peppered with images, anecdotes, memories, aphorisms and parables.

«How well he preaches! We can understand everything.» This praise had come from a

woman in the crowd, and Cardinal Felici, who had heard it with his own ears, had no

difficulty showing how well deserved it was48.

The journalist Jean Bourdarias recalled that this type of preaching by a

Pope was not unprecedented: «Pius X used to give catechism classes on

Sundays in Vatican Square.49»

Beginning with his first general audience on Wednesday, September 6, 1978,

John Paul I preached on humility. Thus he began to purify the Church

from «the pride of the reformers»50.

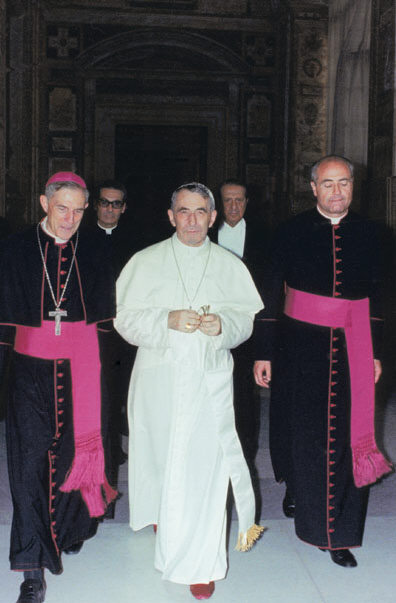

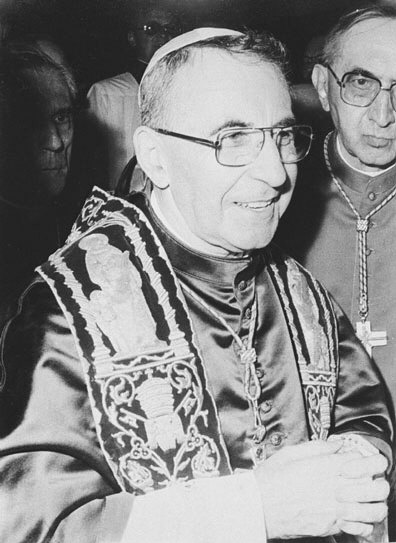

Pope John Paul

I.

«I can assure you that I love you, that I desire only

one thing: to

enter into your service and to place my poor powers, the little that I

have and that I am, at everyone’s disposal.» (Homily of September 23,

1978, in the Basilica of Saint John Lateran; photo AFP). |

«Before God the attitude of the just man is that of Abraham who said: “I am

but dust and ashes before Thee, O Lord!” We must see ourselves as small before

God. When I say, “Lord, I believe”, I am not at all ashamed of feeling like a

little child before his mother; he believes in his mother; and I believe in the Lord,

in what He has revealed to me […].

«I am in danger of saying something outrageous, but I will still say

it: Our Lord loves humility so dearly that He sometimes permits serious sins.

Why? Because those who have committed them and who subsequently repent are

humble. One has no wish to see oneself as a little saint or a little angel

when one knows that one has committed enormous sins. “Be humble!” That is what

Our Lord so strongly recommended to us. Even if you have done great things, you

should say, “We are only unprofitable servants.” But, on the contrary, we all have a tendency to put

ourselves forward. Be humble, truly humble.51»

The audience of September 13, on the Faith, gave a fresh radiance to Catholic truth:

«When the poor Pope, when the bishops and the priests teach

doctrine, they are merely assisting Jesus. This doctrine does not come from us,

it is Christ’s: we are nothing but its guardians, we must simply make it known.52»

What judicious reflections in his speeches! What well-chosen stories to

enlighten souls of good will. Listen to him replying during this same audience

to one of the objections so often trotted out against the Church’s holiness:

«If a mother is unwell, if my mother should become lame, I would only love her

all the more. It is the same in the Church. If there are defects and

shortcomings within her – and there are –, I must not love her any the less for

that.

«Yesterday I was sent an edition of Citta nuova where there was

transcribed a short talk I had given in which I related the story of a British

preacher called McNabb who used to talk about the Church in Hyde Park. At the

end, someone asked to speak and said, “All that is very well, but I

know a Catholic priest who has no time for the poor and who has grown very

wealthy. I also know Catholics who have deceived their wives. I don’t like this

Church which is made up of sinners.” The Father answered, “There’s something in

what you say. But may I make an objection?” – “All right.” – “Excuse me if I am

mistaken, but isn’t the collar of your shirt a little dirty?” – “Yes, so what?” –

“If it’s dirty, it is either because you didn’t use soap on it, or else

because you did use soap but it did no good!” – “It is because I didn’t use soap

on it!” – “Ah well! the Catholic Church has an extraordinary soap: the Gospel,

the sacraments and prayer. The Gospel read and practised, the sacraments

properly celebrated, and prayer well said are a marvellous soap capable of

making us all into saints. But we are not all saints, and that is why we have

such great need of this soap.”53»

His sermon of September 20, on Christian hope, revealed his

deep inner joy at knowing himself «swept up in a destiny of salvation that would

one day open onto Paradise […]. I would love it if you had read an Easter Sunday

sermon of Saint Augustine’s about the alleluia. The true alleluia, he says, will be

sung by us in Paradise. It will be the alleluia of a love that is full. Here

below we sing the alleluia of a love that remains unsatisfied, an alleluia of

hope.54»

Finally, on September 27, he continued his truly evangelical teaching by

speaking of the third theological virtue, charity, as ever with the same joyous

simplicity.

«In a word, to love means making a journey, running with all one’s heart

towards the object loved. The Imitation of Christ says, “He who loves

runs, flies and leaps with joy.” (chapter 42) To love God is therefore to

travel with one’s heart towards God. It is a really beautiful journey! When I was a

child, I was thrilled by the journeys described by Jules Verne: Twenty

Thousand Leagues Under The Sea, From The Earth To The Moon, Around

The World In Eighty Days, etc. But the journeys of love for God are far more

interesting. An account of them can be found in the lives of the Saints. Saint

Vincent de Paul, whose feast we celebrate today, for example, is a giant of

charity. He loved God more than one loves a father or mother, and he himself

became

a father for prisoners, the sick, orphans and the poor. Saint Peter Claver

signified his total consecration to God by signing himself, “Peter, the slave of

the Negroes for ever.”

«This journey also involves sacrifice, but this must not hold us back. Jesus

is on the cross. Do you want to embrace Him? You cannot do less, then, than to

bend over the cross and let yourself be pricked by a thorn from the crown on His

head (cf. Saint Francis de Sales, Oeuvres, Annecy, vol. 21, p. 153). You

cannot act like that good Saint Peter who boldly exclaimed, “Long live Jesus!”

on Mount Thabor where there was joy, but who did not show himself alongside Jesus

on Mount Calvary where there was danger and suffering (cf. ibid., vol. 15, p. 140).55»

In his catechism instructions, the Holy Father re-taught the humble faithful

to believe, to adore, to hope and to love, just as the Angel had done in 1916 for

the three shepherd children, preparing the way for the Queen of Heaven.

In his address to the clergy of Rome on September 7, he visibly sought to

revive in his priests the spirit of prayer, sacrifice and supernatural union

with God:

«High discipline requires a suitable climate. And, above all, recollection.

One day in the railway station in Milan I saw a porter who was sound asleep, his head

resting on a sack of coal propped against a pillar. Trains

pulled away whistling or came to a halt grinding their wheels; the loudspeakers

continually broadcast deafening announcements; passengers came and went noisily.

But he – sleeping on – seemed to say, “Do what you like, but I need to be left

in peace.”

«We priests should behave in a similar manner. All around us there is

incessant agitation; people, newspapers, radio and television drown us in words.

With priestly moderation and discipline we must say, “Beyond certain limits, for

me who am a priest of the Lord, you do not exist. I need a little silence for my

soul. I detach myself from you in order to be united with my God.”56»

This truly evangelical teaching was an invitation to piety, to charity, to

apostolic zeal: once more it was a question of working out one’s salvation, of

pleasing the Lord within through the practice of the virtues, of continuing the

Church’s

tradition of holiness, and then all the rest would be granted in addition.

«HALF

TREMBLING, WITH HALTING STEP».

However, John Paul I was proceeding «half trembling, with halting step»,

as in the vision of the Third Secret, because he professed to accept the

full legacy left by Paul VI and the Vatican II Council. Now the Council’s

novelties, particularly its worldly and temporal humanism wholly directed

towards building the

earthly city, cannot be squared with a divine, Christian and supernatural moral code,

whose essential end is the

acquisition of eternal blessings. What is more, John Paul I’s official adoption

of the doctrines of Paul VI and Vatican II placed him in a weak position to challenge the more revolutionary theories deriving from those

doctrines.

His speech of September 20 shows just how uncertain and perilous was the path

he had taken:

«I should like to speak about a hope that some describe as Christian, but

which is only so up to a certain point. Let me explain. At the Council, I myself

voted in favour of the Conciliar Fathers’ Message to the World. There it was

stated that the Church’s principal task, which is to divinize, does not dispense

her from the duty of humanizing. I voted for the constitution Gaudium et spes. I

welcomed with emotion and enthusiasm the encyclical Populorum progressio. I

think that the Church’s magisterium can never be insistent enough in presenting and

recommending the solution to the great problems of freedom, justice, peace, and

progress; and Catholic laymen can never fight hard enough to provide a

solution to these problems.

«But it is an error to affirm that political, economic and

social liberation coincides with salvation in Jesus Christ; that the Kingdom of

God is identified with the Kingdom of man; that “Ubi Lenin, ibi Jerusalem; where Lenin is, there

is Jerusalem.”»

He thus took issue with the thesis developed by liberation

theologians, without however disowning conciliar humanism.

«At Freiburg in Breisgau», he went on, «there has been taking place over these last

few days the 85th Katholikentag on the theme: A Future of

Hope.

They spoke of

making the world a better place, and the word future was full of hope.

«But if from hope for the world one passes to hope for each

individual soul, then one

must also speak about eternity. Recalling his celebrated conversation with his

mother Saint Monica on the coast at Ostia, Saint Augustine said, “Forgetting

the past and gazing towards the future, we pondered what eternal life would be

like.” (Confessions, 9:10) Now that is Christian hope. That is what Pope John

used to think about, and that is what we ourselves think about when, with

the catechism, we make this prayer: “My God, of Thy bounty I hope for eternal

life and the graces necessary to merit it through the good works that I am bound

and willing to perform. My God, grant that I may not be confounded for

eternity.”57»

Very much impressed by so-called modern ideas, the new Pope could not

clearly see how to resolve certain doctrinal and moral difficulties. In his

homily of September 23, in Saint John Lateran’s, he confided this fact with great

modesty: «The second reading, taken from the last chapter of the Epistle to the

Hebrews, is applicable to the faithful in Rome. It was chosen by the master of

ceremonies. I confess that what it says about obedience embarrasses me a little.

It is difficult nowadays to be convincing when one weighs the rights of

the human person against the rights of authority and the law!58»

The beloved Pontiff lacked the mastery needed, the expertise of one who had

conceived a vast synthesis that would have allowed him to oppose modern errors

with a renewed body of Catholic doctrine.

Nevertheless, under the leadership of such a Pope, the differences in the

Church might have been regulated in a climate of true charity. «John Paul I had

none of the arrogance of the innovators», observed the Abbé de Nantes, «none of

the incredible dogmatism of the new theologians and reformers assured of their

infallibility in everything, even against the age-old Church and her

magisterium.59»

Had not Albino Luciani admitted, «with his customary honesty and simplicity»,

that upon one point in the Council his conscience had rebelled? And the Abbé

de Nantes had drawn an important lesson from this:

«Between John Paul I and ourselves, between the legacy of John and Paul which

he had professedly espoused and our League of the Counter-Reformation, there remained

an insurmountable opposition on precise, significant points of the faith. We

could not, and shall never be able to, accept as a new dogma the so-called

social right of Man to religious liberty. No more can we accept the cult of Man

proclaimed by Paul VI before the whole Church on December 7, 1965, for the

closing of the Council. Consequently, we had been told for fifteen years, both

in France and in Rome, that we were pursuing a dead end.

«However, John Paul I has reopened the path before us by his simple words of

honesty and humility. His words alone are the unmaking of heresy, they have

unblocked the conciliar impasse. By themselves these words would justify the all

too brief reign of the Pontiff on Saint Peter’s throne, in the unanimity of the Church unanimously

recognising herself in him. Confessing his inner struggles during the Council and the difficulty he had had in coming round to the theses

of the innovators, particularly the theory of religious liberty, he openly

admitted, “The most difficult thesis for me to accept was that of religious

liberty. For years I had taught the thesis that I had learned in Cardinal Ottaviani’s course on public law, according to which error has no rights. I

studied the problem thoroughly and finally I became convinced that we had been

mistaken.60” Another version of the same admission reads: “They

persuaded me of

my error.61”

«At one blow, the Pope’s candour restored everyone’s right to be heard, even

after Vatican II, without any fraudulent excommunications. The true proportions

of the present drama were reinstated, namely that some had ended up allowing

themselves to be persuaded (or else had managed to persuade themselves) that the

Church had previously been mistaken, while others remained persuaded (or else came ultimately to understand) that

the ones who had

been mistaken and

deceived us were the innovators of this Council rather than the Church of all

time. To admit the possibility of error, whichever side the mistake actually

lies on, is to restore peace to the Church by relegating these

difficult questions to the domain of free opinion pending a dogmatic Vatican III

or the Pope’s infallible definitions.62»

John Paul I was certainly proceeding «with halting step», but he did so

whilst manifesting an extraordinary gift and charisma for touching and

rekindling

hearts. His exhortations, like a shockwave, led to an emulation of

spiritual conversion, of reconciliation between brothers and, even beyond this,

of peace for men of good will.

On Sunday, September 24, at the Angelus, he spoke of «the violence

continually experienced by our poor, troubled society». He cited the pitiful

case of Luca Locci, a «child of seven, kidnapped three months earlier». Then he

continued:

«People sometimes say, “We live in a society that is totally rotten and

dishonest.” That is not true. There are still plenty of honest and decent people

around. We should rather be asking ourselves: what needs to be done to improve

society? Let each one of us make an effort to be good, so that the goodness we

spread around us, totally permeated with the meekness and love taught us by

Christ, becomes infectious. Christ’s golden rule was, “Do not do unto others

what you do not wish them to do to you; do to others what you wish them to do to

you; learn from Me because I am gentle and humble of heart.” He Himself was always

giving. When they put Him to the cross, not only did He pardon His executioners,

He also excused them: “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.”

That is Christianity. If such sentiments were put into practice, they would aid

society greatly.»

John Paul I then went on to talk about the thirtieth anniversary of the death

of Georges Bernanos, alluding to his book Dialogues des Carmélites, which

gave him an opportunity describe their martyrdom:

«In 1906, here in Rome, Pius X beatified the sixteen Carmelite Nuns of Compiègne, who died as martyrs during the French Revolution. The tribunal

condemned them to death for “fanaticism”. One of them, in her simplicity, had

asked: “My Lord Judge, if you please, what does fanaticism mean?” And the judge

replied, “It means your stupid adherence to religion.”

«“Oh my Sisters”, she then exclaimed, “did you hear that? We’ve been

condemned for our attachment to the faith. What happiness to die for Jesus

Christ!”

«They were taken from the Conciergerie Prison and made to climb up onto the

deadly

cart. On the way they sang hymns. When they arrived at the guillotine, they

knelt down, one after the other, before the Prioress and renewed their vow of

obedience. They then intoned the Veni Creator. But the song became

fainter and fainter as the heads of the poor Sisters fell one by one

under the guillotine. Remaining behind until last, the Prioress, Mother Thérèse

de Saint-Augustin, pronounced these final words, “Love will always be

victorious; love is capable of everything.63”

How true. It is love, not violence, that can achieve everything.

«Let us ask Our Lord for the grace of a new wave of love for our neighbour,

one that will submerge this poor world.64»

Thus did the Holy Father remember this poor child, Luca Locci, a kidnap

victim. Well, on the following night, just as on Christmas night in the

Pastorales Provençales, she was freed by her kidnappers. Such were the

wonderful fruits of Albino Luciani’s radiant goodness and evangelical teaching.

THE

CHOSEN ONE OF THE

IMMACULATE

On September 3, during his enthronement ceremony, John Paul I spoke a few words at

the end of his homily expressing his tender devotion for the Immaculate. He

consecrated himself to Her with all his heart: «We commence our apostolic

service by invoking as the splendid star who will enlighten our path, the Mother

of God, Mary, Salus populi romani and Mater Ecclesiae, She for whom

the liturgy has a special veneration in this month of September.

«May the Virgin who guided with a motherly tenderness my life as a child,

seminarian, priest and bishop, continue to enlighten and direct our steps, so

that, having become the voice of Peter, with our eyes and heart fixed on Her Son

Jesus, we may proclaim before the world, with a joyous steadfastness, our

profession of faith: “Thou art the Christ, the Son of the living God.” (Mt

16:16)65»

That day, he received the respects of the Cardinals with his wonderful

cordiality. To each he said a kindly word, and above all he begged their

prayers: «Eminence, remember to say an Ave Maria for the Pope.66»

We rediscover his filial devotion to Our Most Blessed Mother in Heaven in

his Apostolic Letter of September 24, addressed to his dears sons in Ecuador:

«We know that you are currently celebrating the third National Marian

Congress on the theme “Ecuador for Christ through Mary.” Taking this

theme as your starting point, make progress in life and apostolic action. May Mary, the Mother of

Christ, the Mother of the Church and the most tender Mother of each of us,

always be your model, guide and path towards the Elder Brother and Saviour of

all, Jesus. And may She likewise, in these times both difficult and yet full

of hope, be the star of evangelisation in Ecuador. 67»

What a programme! The path proposed to the Church by John Paul I was the

Virgin Mary Herself. The Holy Father had appointed Cardinal Ratzinger, the then

Archbishop of Munich, as the Apostolic Legate to this Marian Congress. The

quotation from Saint Augustine accompanying the mission briefing was clearly

chosen deliberately as the very expression of his soul:

«At Guayaquil let there shine out with a new Marian splendour that mystery

about

which Saint Augustine exclaimed in wondrous admiration: “What mind could

contemplate, what tongue could express the fact that not only did the Word exist

in the beginning without any principle of birth, but also that the Word was made

flesh, that He chose a virgin to become His mother, a mother who remained a

virgin... What can this be? Who could tell of it? Who could remain silent about

it? Strange to say, but what we cannot express we cannot remain quiet about

either; we loudly preach what our intelligence fails to grasp.”68»

John Paul I proclaimed the Blessed Virgin Mary “Heavenly Patroness of the

City of Itabirito”, in the diocese of Mariana in Brazil, under the title of

Our Lady of the Safe Journey, and he elevated the sanctuary of Bedonia in

Italy, dedicated to the Virgin of Consolation, to the rank of a minor

basilica. How joyfully these two titles must have sounded in his ears!

We know not whether, during the thirty-three days of his pontificate, he

ever read the Third Secret, kept in the palace of the Holy Office, and what his

intentions were in its regard.

Before making it public, he doubtless wished to revive devotion to Our Lady

of Fatima amongst the faithful. On July 11, 1977, he had spoken to Sister Lucy

about the “Marian Tour” which was to commence in Italy, in preparation for the

celebration of the twentieth anniversary of that nation’s consecration to the

Immaculate Heart of Mary69.

And indeed, in the autumn of 1978, a statue of the Virgin of Fatima began to

wend its way throughout the dioceses of Italy on a journey that took two years.

The truth is that the thought of Fatima and Sister Lucy never left him. He

spoke about this to Don Germano Pattaro, a theologian from Venice, whom he had

invited to Rome to be his adviser:

«It is something that has troubled me this whole year. It has robbed me

of my

spiritual peace and tranquillity. Ever since that pilgrimage, I have never

forgotten Fatima. What Sister Lucy told me has become a weight on my heart. I sought

to convince myself that it was all an illusion. I prayed to forget about it. I would

liked to have shared all this with someone close to me, to my brother Edoardo, but

I never managed to. The thought was just too huge, too embarrassing, too

contrary to my whole being. It was unthinkable, and yet Sister Lucy’s prediction

has turned out to be true. Here I am. I am Pope.

«It is repugnant to me to speak of these things, but I do it in order to open my soul

to you, to confide to you that I never wanted to become Pope.

«If I live, I shall return to Fatima to consecrate the world and particularly

the peoples of Russia to the Blessed Virgin, in accordance with the instructions

She gave to Sister Lucy.70»

So John Paul I had decided to accomplish the request of Our Lady of Fatima

in an act of obedience and filial love towards Her Immaculate Heart. It is not

surprising that he spoke of a consecration of the world and of the

peoples of Russia for, at that time, the Virgin Mary’s exact request, namely

the consecration of Russia and of Russia alone, was little known, having

been widely misrepresented. Let us admire rather his inner dispositions: Pope

John Paul I had resolved to perform the consecration «in accordance with the

instructions given by the Blessed Virgin to Lucy». He had therefore entered into

the divine plan with a childlike docility. In his humility, he wanted to do what

the Blessed Virgin had requested, in exactly the manner She had requested it,

and for the sole reason that She wished it thus.

«If I live...», he had said to Don Pattaro, as though he had been warned that he

would not live. In fact everything indicates that this is precisely what he had

learned from his conversation with Sister Lucy.

PIERCED

WITH «ARROWS»

The Secret of Fatima shows us «a Bishop dressed in White killed by a

group of soldiers who fired bullets and arrows at him».

In his exegetical commentary on the vision, Brother Bruno de Jésus writes:

«This “group of soldiers who fired bullets and arrows at him” represents the

armies of Gog and Magog, symbolic names given by the Book of the Apocalypse to

the nations conspiring against the Church at the end of the times: “When the

thousand years are over, Satan will be released from his prison and will come

forth to seduce the nations from all four quarters of the earth, Gog and Magog,

and mobilise them for war, their numbers being as great as the sands of the sea;

they went up throughout the entire land and besieged the camp of the saints,

the beloved City.” (Ap 20:7-8)

«Already prophesied by Ezekiel, these armies are equipped with bows and

arrows (Ez 39:3 and 9)!71»

It is important to remember the biblical and symbolic significance of arrows

in the eternal plot of the wicked against the Servant of God. Let us quote Psalm

64:

Hear my voice, O God, in my

complaint;

Preserve my life from dread of the enemy,

Hide me from the secret plots of the wicked,

From the scheming of evildoers,

Who whet their tongues like swords,

Who aim bitter words like arrows,

Shooting from ambush at the blameless,

Shooting at him suddenly and without fear.

Jeremiah was the emblematic, figurative victim of this conspiracy, foreshadowing

the suffering Messiah, Our Lord Jesus Christ exposed to the conspiracy of the

Pharisees and Herodians from the very first day of His public life:

They bend their tongue like a

bow;

Falsehood and not truth

Has grown strong in the land;

For they proceed from evil to evil,

And they do not know Me,

Says the Lord. (Jr 9:2)

The «arrows» are the malevolent remarks of false brothers: «Their tongue is a

deadly arrow; the words of their mouths are nothing but deceit; they speak

peaceably to their friends, but in their hearts they lay a snare for them.» (Jr

9:7)

During his pontificate John Paul I was pierced by murderous

«arrows». Whereas

the simple folk in Rome were moved and enlightened by his short, joyful

catechism lessons, the mainstream journalists mocked his preaching.

In France Le Monde meanly insinuated that the popular character of his

catechesis and his aversion for the contortions of theology «arose from a lack

of study on his part». The Minute contained this headline: «Don Camillo in the

Vatican.» The Informations catholiques internationales distinguished

itself by its perfidy: «Seen from close up, his ever-present smile lacks that

touch of candour apparent in photographs; it expresses something akin to

wiliness. An Italian friend explained this to me on the telephone, and he

understood it as a compliment: “He is furbo”. By which he meant not a

wicked rogue, as in the French fourbe, but someone who was crafty all the

same.72»

It was not only attacks from malevolent journalists and modernist theologians

now feeling threatened that the Holy Father had to put up with. He was

persecuted by several prelates based in the Curia. Andrea Tornielli, his

biographer, writes: «His simple style of preaching at the Wednesday audiences

drew criticism and fierce comments from the Vatican establishment.73»

«His naive questions», writes J.-J. Thierrry, «his spontaneity, his

indifference to formality, his ignorance of palace etiquette and of the Pope’s

job, gave rise all around him to pitying smiles, condescending derision, indeed

suspicions that were already hostile.74»

John Paul I suffered all this privately, but it was not the first time he had

experienced acerbic criticisms of this kind. In Venice, let us remember, he had

come into conflict and dispute with the progressivist minority of his

clergy.

«Msgr. Luciani», writes Don Francesco Taffarel, «encountered difficulties and

trials, often painful, which afflicted him; but he strove to conceal them,

disguising them under a smiling face. He was in the habit of saying: “It is

enough for me if God is happy with me. What I think of myself, I must play down;

what others think of me, I must overlook; but what God thinks of me, that alone

is what matters to me.”75»

Sometimes, almost overwhelmed, he would nevertheless react with his

supernatural spirit: «Say a Hail Mary for me», he would ask those close

to him, «so that the devil may not carry me off and that I may not sit down on

the side of the road. Let us forge ahead. I did not move even my little finger to occupy this post. In fact my desire

is to relinquish it, to retire, but let us go forward with confidence.76»

Sister Vincenza Taffarel, already in his service at the Archbishop’s house in

Vittorio Veneto and at the Patriarch’s house in Venice, had followed him to

Rome. When she spoke to him one day about the enthusiasm he was generating and

the applause of the faithful, he replied: «Trust not a crowd that

cries “Hosanna” and then just as easily “Crucify him”. It is on God that we must

count, and it is through Him that things are done.77»

Rapidly did the Abbé de Nantes, in that month of September 1978, understand

the imminence of the drama: the modernists, disturbed by the sudden resurgence

of Tradition, were looking to compromise the Pope, or to discredit him and bring him

down. «A confrontation was going to take place, one that was inevitable, implacable and

deadly.» It would be «a great dramatic confrontation between those who hold

the faith and those who are perverting it, between those who are building up the Church

and those who are destroying it, between the men of God and the mercenaries of

Satan, for that is what they are78».

The theologian of the Catholic Counter-Reformation had discerned what was still

hidden from everyone’s eyes. Several of John Paul I’s parables «heralded the

controversy to come, as did Christ’s terrifyingly clear allegories in Jerusalem,

which made the scribes and Pharisees grind their teeth, as they saw that

they had been exposed, and so made them want to kill Him. The sublime little

parable about the Milan porter79

ostensibly teaches religious recollection and the worship of God even amidst the

din of our great cities. But the intimate disciple – as well as the enemy whose

hatred gives him a certain lucidity –understood therein an invitation to despise the world

and its excessive demands, for God alone must be the master of all things in His

Church.80»

On September 23, in his homily given in the Basilica of Saint John Lateran, John

Paul I announced that he would fulfil the duties of his charge by imitating

Saint Gregory the Great, one of his predecessors on the see of Rome:

«The third book of his Regula pastoralis has as its theme:

Qualiter doceat, How the pastor should teach. In forty chapters,

Saint Gregory indicates in a concrete way various forms of instruction according to

the circumstances, such as social condition, age, health, and temperament of

the audience. Poor and rich, cheerful and melancholic, superiors and subjects,

learned and ignorant, bold and timid, and so forth; all are there in this book.

It is like the valley of Jehoshaphat. At Vatican Council II, what was called the

“pastoral approach” seemed to be something new. It no

longer referred to that which was taught by the pastors, rather to that which the pastors

did to respond to men’s needs, aspirations and hopes. This new approach

had already been applied many centuries earlier by Saint Gregory, both in preaching and

in governing the Church [...].

«I would also like to see Rome give a good example in matters of liturgy, of

a liturgy celebrated devoutly and without ill-placed “creativity”. Certain

abuses in the liturgy have, by reaction, fostered attitudes

that have led to positions that are in themselves untenable and

contrary to the Gospel. By appealing with affection and hope to everyone’s sense

of responsibility before God and the Church, I would like to be able to be

assured that every liturgical irregularity will be carefully avoided [...].

«In Rome I shall put myself in the school of St Gregory the Great who writes:

“The pastor should, with compassion, be close to each of those who are subject

to him. Forgetful of his rank, he should consider himself the equal of his good

subjects, but he should not fear to exercise the rights of his authority against

the wicked.”81»

The Abbé de Nantes understood the import of such a warning: «Words long

meditated upon, make no mistake! For the good they were the announcement of an

exceptional season of gentle charity, of warm understanding and of an unaffected

papal welcome, a renewal of patristic times under the easily discernible

influence of Rosmini. To the bad – ah yes, the bad exist and they need to be

accorded the charity of some rather more robust treatment – to the bad his words

represented the authoritative imposition of respect for the divine faith and law,

assisted, if need be, by the threat of ecclesiastical sanctions.82»

The journalist Jean Bourdarias revealed that John Paul I had lost his smile,

with his collaborators, when he learned of the files left behind by Paul VI83.

The Holy Father was to discover «that total leukaemia of disorder, apostasy and

immorality, all of which had been spread, officially installed and encouraged from

the top to

the bottom of the hierarchy»84.

John Paul I had discovered the files containing requests for laicisation and dispensation from celibacy. Paul VI had granted them, from the very

beginning of his papacy, at an average rate of ten per day85.

In Vittorio Veneto, and later in Venice, the defections of certain of his priests

had been like a wound in Msgr. Luciani’s heart, even causing him sleepless

nights.

He therefore took the courageous decision to arrest this haemorrhage. «John Paul

I asked for an immediate revision of the criteria used for granting priestly

dispensations, as he considered the number of requests reaching his desk to be

excessive.86»

But he had heavier concerns: he found himself facing insurrection

from senior prelates in the Curia who neglected his orders and contravened his

directives. Msgr. Giuseppe Caprio, Substitute of the Secretariat of State, recalls

one especially dramatic evening:

«There was a very important problem to resolve. John Paul I was keen to

handle it personally. Just when he thought he was getting there, the affair

began to take a different turn. It was only natural that he was concerned, as I

was myself. We had drawn up a plan and now someone had blown apart this plan.87»

Sister Vincenza witnessed a scarcely believable scene, one that allows us a glimpse

of the terrible pressures and threats that John Paul I had to suffer.

«While I was at Rome», she recounts, «I used to clean the sitting room around 8

a.m., for there was no one there at that time. One morning, making my usual

visit,

I was too late to notice that the Holy Father was already there. His posture

revealed his profound affliction. By his side was his secretary. I made my

apologies and hastily withdrew. Nevertheless, I had time to hear his secretary

saying to him: “Holiness, it is you who are Peter! It is you who wield authority! Do not let

yourself be intimidated...” That phrase spoke volumes.88»

«Poor Holy Father!» ... so spoke the Blessed Jacinta, a true prophet.

John Paul I was in conflict with Cardinal Sebastiano Baggio over the

nominations of new bishops to several diocesan sees, including that of the

Venice patriarchate. «The Pope», writes Andrea Tornielli, «had two possible

candidates in mind for Venice: the Jesuit Bartolomeo Sorge, then director of the

Civilta Cattolica, the Jesuit monthly journal, and the Salesian Egidio

Vigano. But the Congregation of Bishops, headed by Cardinal Baggio, had

different views and presented the Pope with three candidates who were already

bishops.»

Andrea Tornielli reports the testimony of Don Licio Boldrin. «In 1981»,

recounts this Venetian parish priest, «I met Cardinal Agostino Casaroli outside

the Church of the Piazza del Gesù. I stopped to greet him and we spoke

about Pope Luciani. “You know”, the Cardinal told me, “that the Pope had to

find a successor for Venice and that he already had a number of names in mind.

The Congregation of Bishops also had their own suggestions to submit to him. John Paul

I insisted in one particular direction, the Congregation in another. Cardinal Baggio therefore asked me to win the Pope over, assuring me that the

candidatures proposed had been thoroughly examined, and adding, You know, we

don’t want anyone to speak ill of the Pope afterwards. So the following

morning I took the liberty of telling Pope Luciani, Holiness, try to follow

the Congregation’s directions. At least, like that, the Pope will not be

criticised. He took me by the hand and said, Excellency, don’t talk like

that, for if I needed to be wary of those who speak ill, I would have

dismiss you from here immediately.”89»

The Pope confided to Don Pattaro, «I am beginning to understand things that I

had previously not noticed. Here, everyone speaks ill of each other. If they

were able, they would even speak ill of Jesus Christ.90»

Thus it was that, in the «great city half in ruins», John Paul

I encountered «corpses» on his path, men for whom he could do

nothing but «pray».

THE CONSPIRACY, IN ALL ITS TRUTH

The sudden death of the beloved Pope, on the night of September 28 to 29,

1978, immediately aroused grave suspicions amongst the citizens of Rome. In his

editorial of October 1978, entitled “The Saint that God gave us”, the Abbé de

Nantes wrote:

«“Hanno mazzato il papa! They have killed the Pope!” That is what

they always whisper in Rome every time a Pope dies. But this time the rumour

has become so widespread that even La Croix is informing its readers of it:

“They killed him,

say the Romans. He was too nice, too kind.” It then rather awkwardly adds: “By

they is doubtless [without the slightest doubt!] meant the cares of the universal

Church, and even more so the administration of the Vatican with all its complex

machinery... For it appears that John Paul I collapsed under the weight of the

papal office, each new day forcing him to confront new dossiers with

difficult problems to resolve.” (La Croix, October 1-2)

«Let’s suppose we believe Jean Potin: what

killed the Pope was doubtless the system, the dossiers, the problems, and not those

who stand accused by the people of Rome. Will we ever know? God has permitted the death of

His servant, that is for sure, and the Church will continue down the same path

despite her enemies. For myself, in this murder I make no distinction between

the dossiers and those who brought him the dossiers. What killed

the holy Pope John Paul I was opening the secret dossiers of Paul VI.

«As for his other crosses, he would have borne these. Yes, Bernert of

L’Aurore is right: the genocide coldly perpetrated by the Syrians against

the Catholic Lebanese community was one such cross, and a heavy one at that: “It is

imperative to stop this massacre”, said this great-hearted Pope on the very

morning before his death, “to intervene as rapidly as possible on behalf of the

Christians. I have just written to President Carter along these lines. We cannot

leave these people to die.” (L’Aurore, October 3) It made him weep, he

wanted to go to Beirut himself to be with his children in that bombed town

[...].

«But the Vatican dossiers are truly of a different order. They reveal

the immense auto-destruction of the Church and the smoke of Satan eloquently

referred to by the previous pope, the full extent of which Cardinal Luciani had never

previously considered. He had left all such matters to

supreme authority, while he got on with fulfilling to perfection his own

responsibilities, holding out his hand to everyone in his Venice patriarchate,

but without tolerating the least disorder. Now what killed him was this: to have

seen that he had to quit the peaceful paths of a prudent and professedly

conciliar reformism in order to cut into the quick and combat the postconciliar

disorder. If he felt himself too weak for such a struggle, then it is

true that this was the cause of his death; but if, on the other hand, he had

determined to immediately put up a fight, then perhaps they may indeed have killed him.91»

Although the Abbé de Nantes did not at the time know the true reasons for

John Paul I’s murder as we know them today, he had at least a presentiment

of them when he declared in this same editorial: «Had he lived a month

longer, John Paul I would have started cleaning out the Augean stables,

beginning with the Vatican. And it is for this very reason that he was not

allowed to

live. He was already aware of this, and yet he continued on his path with a smile in his eyes and the

firmest resolve in his heart.92»

The Abbé de Nantes’ intuitions and suspicions were confirmed over the

following months by information privately communicated to him93,

then by the research of the writer Jean-Jacques Thierry94,

but above all by the implacable demonstration published in May 1984 by the English

journalist David Yallop in his book In God’s Name95.

After three years of secret investigation, this seasoned investigator revealed

how it was money that hatched the conspiracy against John Paul I.

Yallop, whose information was «verifiable on a thousand points»96,

revealed the precise reasons and circumstances behind the Holy Father’s

assassination by poisoning: «He denounces the six presumed partners and authors

of this crime, men who were also totally bound up in a tissue of other sordid

and financial crimes, both before and after. It is a fine and intelligent piece

of work... He determines their motives and then, in an amazing fashion, minutely

reconstitutes Cardinal Jean Villot’s activities in the twelve hours following the

crime in order to make it look like a natural death.97»

In his gripping review of this work98,

the Abbé de Nantes presented the remote cause of the financial embezzlement and fraud in which the Vatican was directly implicated, and

which

John Paul I had stood up against. In the Lateran Treaty agreed between Pius XI and

Mussolini in 1929, the Church had received a colossal fortune in compensation

for renouncing her rights over the Papal States: the lira equivalent of 81

million dollars at the time.

«The Vatican thus became a financial consortium, an element of that

“anonymous and vagabond fortune’ so vigorously denounced by the Duke of Orleans

in 1900, which knows of no lucrative activity other than speculation on the

money market, stockjobbing, that vicious game of seesaw played out on the international

markets with industrial and commercial stocks, the laundering of dirty money,

the evasion of capital taxes, etc, all of which activities are simply illegal

or absolutely criminal.

«The German ecclesiastical tax, the Kirchensteuer, instituted under

the Hitler-Pacelli Concordat of 1933, added its own powerful and regular income

to the already large flow of capitalist profit brought in through the Italian

treasury. An easy speculation on gold at the approach of the war, which Pius XI

knew to be unavoidable, allowed the financial power of Vatican Incorporated to be

increased in a fabulous manner.

«In June 1942, all the assets and real estate entrusted to the Church for her

pious charitable and apostolic works were entered into the dance of the stock market

with the creation of the Institute for Religious Works. This was a cover for an

audacious misuse of the gifts of the faithful, now no longer being used in

conformity with their donors’ primary intention but for an intermediate one:

speculation. The IOR is no longer a religious administration, but simply a bank,

the Vatican Bank, receiving stolen goods and exploiting the gifts of the faithful without

their knowledge.99»

In the course of that same year, 1942, Mussolini dispensed the Holy See from

the requirement to pay tax on its dividends.

However, twenty-five years later, in 1967-1968, the Italian State wished to

abolish this fiscal exemption. Paul VI therefore called upon Paul Marcinkus, a

native of Chicago, and on Michele Sindona, a Sicilian mafioso, to

organise a flight of capital of such enormous proportions that Italy was plunged

into an economic crisis. This was the starting point of an infernal web of

corruption so rigorously reconstituted by David Yallop that no one has ever been

able to repudiate it in the smallest detail: systematic blackmail, corruption,

and finally the Italian solution which consists in creating a climate of intimidation

through murder,

sometimes killing a magistrate who wants to know too much, sometimes a troublesome

detective.

In 1978 the mafiosi who had been feeding their own bank accounts by

siphoning off funds from “Vatican Incorporated”, were tracked down by the

international police and prosecuted by the Italian and American justice systems

for theft, forgery, illegality, crime and even for murders already committed under

the cover of “Vatican Incorporated”. «In August, pressed hard on all sides,

Roberto Calvi saw his empire breaking up, under suspicion, threatened. He felt the

need for a change of air in South America where Licio Gelli was also looking for

a little peace and quiet. Meanwhile their friend Michele Sindona lay in a New

York prison, trembling at the imminent prospect of being extradited and handed

over to Italian justice. One common point united them: as long as Bishop

Marcinkus stayed put in Vatican Incorporated, they could breathe. Were he to

leave, it would mean for each of them, in one way or another, a harsh return to

reality, ruin, prison or suicide... or all three misfortunes together.100»

Yallop writes: «When the cardinals elected Albino Luciani to the Papacy on

that hot August day in 1978, they set an honest, holy, totally incorruptible

Pope on a collision course with Vatican Incorporated.101»

A pope who had not forgotten how his priests and the poor were robbed by the

Milanese and Vatican mafia when the Banca cattolica del Veneto was sold,

nor all that he had learned from his friend, Cardinal Benelli102.

«The irresistible market forces of the Vatican Bank, APSA and the other

money-making elements were about to be met by the immovable integrity of Albino

Luciani»103. Those

directing the Vatican Bank were Cardinal Villot and Archbishop Marcinkus, their

accomplices Michele Sindona and Roberto Calvi, all from the “P2 Lodge” or

affiliated thereto, and their protector Licio Gelli, its Grand Master.

The day after his election, «on Sunday, August 27th»,

recounts Yallop, «John Paul I asked Villot to continue as Secretary of State for

“a little while, until I have found my way.”»104

This provisional measure constituted in itself a silent threat. In this manner he kept

his enemies under his thumb and within his sight while he contemplated the regal

blow that would bring them down for certain, remarks the Abbé de Nantes.

As we have already stated, on that very day John Paul I ordered his

Secretary of State to re-examine all the Vatican’s financial operations. The

Pope, after having read and studied his report, would then take any measures

he deemed necessary.

On September 12 «a scandal sheet landed on the Holy Father’s desk claiming to

reveal the names of 121 members of the Roman Curia registered as Freemasons.

Among others: Cardinals Villot, Baggio and Poletti, Msgr. Casaroli, Bishop

Marcinkus and his confederates, and Pope Paul’s secretary, Pasquale Macchi...

One man was apparently the cover for them all: the Secretary of State, Jean

Villot!105»

(continued below)

|

Patriarch Albino Luciani on

a pilgrimage to Lourdes, Spring 1971. |

|

The Basilica of Our Lady of the Rosary,

at the Cova da Iria. |

|

On July 10, 1977, Cardinal Luciani

celebrates Mass at Fatima, in front of the Basilica, before thousands of

pilgrims gathered on the esplanade. (Archives of the Sanctuary of Our Lady of

Fatima)

|

|

September 5, 1978. John Paul I welcomes Msgr. Nikodim,

Orthodox Metropolitan of Leningrad, who would die suddenly during the

audience. The Pope, kneeling beside him, would then recite prayers for the

absolution of his sins.

On September 7, in his address to Rome’s clergy, John Paul

I would temporarily abandon the text of his talk to declare with great

emotion: «Two days ago, the Metropolitan of Leningrad died in Our arms. I

was just replying to his address. I assure you that never in my life

have I ever heard such beautiful words on the Church as his. I